Lobsang Jinpa, the monk activist

Lobsang Jinpa was awarded the Reebok Human Rights Award in 1988

Although I was born two decades after China’s invasion of Tibet, my life was shaped by protesting for my country’s freedom. I come from a small village near Shigatse in Ü-Tsang province, Tibet’s second biggest city, and when I was a child the Cultural Revolution was ravaging my country. Under its slogan “Smash the Four Olds”, the Chinese government attacked Tibet’s old ideas, culture, customs and habits. Anything representing Tibetan culture, including thousands of Tibet’s ancient monasteries and Buddhist scriptures, was targeted for destruction.

During my childhood Chinese police would randomly raid our house to look for banned objects, such as the Dalai Lama’s photo. Red clothes were banned as red is the colour of a monk’s robes. My mother was both deeply religious and smart, and used to hide His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s photo behind Mao Zedong’s photo on the altar in our prayer room. I lived in constant fear.

We did not have enough food to eat and I was hungry all the time. Most Tibetans, including my parents, were once farmers and nomads, but the Chinese government took away our land and we were no longer able to produce our own food. Thousands died from famine. My parents were forced to attend struggle sessions; these were public gatherings where Tibetans considered enemies of the Chinese Communist Party were humiliated and abused. These Tibetans included monks and nuns, the elite and the wealthy middle class. Thousands were sent to labour camps and imprisoned.

At school, Tibetan language was replaced by Mandarin and lessons on Tibetan culture were replaced by the study of Marxism and Chinese history. My classmates and I protested, boycotting those classes. All I wanted was to become a monk.

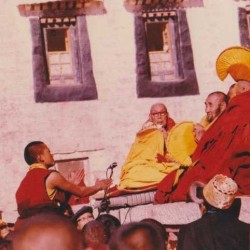

In 1982, aged sixteen, I joined Sera Monastery in Lhasa. There I learned Buddhist philosophy, gained a deeper understanding of Tibetan culture and history, and grew interested in politics. In my monastery room, I wrote about the human rights situation in Tibet. By the early 1980s, economic and social reforms were taking place in China under the new leadership of Deng Xiaoping. Small changes were also seen in Tibet. For instance, more foreign tourists were able to visit Tibet. This created the first opportunity for Tibetans like me to smuggle information to the outside world. The tourists would give me photos of the Dalai Lama, and I, in return, gave them information on what was really happening in Tibet.

As a young monk debating at Sera Monastery, Lhasa

The historic protests in Lhasa in 1987 that changed my life forever

On 21 September 1987, the Dalai Lama announced a “Five-Point Peace Plan for Tibet” in his address to the US Congressional Human Rights Caucus. He called on the Chinese government to start negotiating on the future status of Tibet. China opposed his proposals and on 27 September, a protest led by the monks of Drepung Monastery erupted in the heart of Lhasa. In my room at Sera Monastery a group of monks were making plans to join that protest. On October 1st, Chinese National Day, we too took to the streets. The Chinese government claimed that Tibetans did not support the Dalai Lama; we wanted to set that straight.

We took to the streets with five messages: that Tibet was an independent country; that the Dalai Lama was our leader; that China must get out of Tibet; that China must respect international law; and that all political prisoners in Tibet must be released. We set a single condition for the protest, that it must be peaceful. This was the first time a protest in Tibet was witnessed by foreign tourists. They took our story to the world and the international media and generated wide support for our freedom struggle.

I was a young man and believed Tibet would change forever with that protest. People poured into the streets from every corner of the city, but the police came, too, and they crushed our protest. Although they beat us and arrested us, our spirits remained high. Then we heard a senior police officer shouting “Fire!” from the top of a building and the shooting began. I saw Buchung, a monk from the Tsug Lag Khang temple, being shot in the head. I saw Lobsang Gelek, a monk from my own monastery, shot in the heart; he had been standing right next to me. I lifted his head from a pool of blood. His eyes had turned blue and his forehead was smashed. For years, I dreamed of that scene.

Eighteen Tibetans, including a child, were killed that day. They were all protesting peacefully, all demanding basic freedom in Tibet.

I was badly beaten, given an electric shock to the neck and fell unconscious. This might have saved me from being shot. I found myself in a Tibetan family’s house and went into hiding, fearing arrest.

The police had gone to my monastery, seeking information on the protest’s organisers. In my room they found documents on the political and human rights situation in Tibet and others about the protest. Planning meetings had been held in my room. A big reward for my capture was announced; a Japanese-made truck, popular in Tibet at the time.

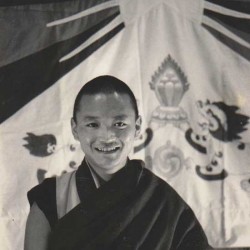

After eight months in hiding – sheltered and fed by Tibetan families – I decided it was time to flee for India. Others helped arrange papers to get me out of the country. I arrived in Dharamsala in the summer of 1988. Within two hours, I met His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, and briefed him on what had happened during the protest.

Posing for a photo after coming into exile

Working as a journalist in Dharamsala

The following year the Tibetan government-in-exile asked me to join His Holiness and a small group of Tibetans to speak at a hearing in the German Parliament. I told the Dalai Lama about the note I had left in my monastery room for Chinese officials before I went to the demonstration. It said ‘Under the current political circumstances in Tibet I am not willing to talk to you, but I will see you at the United Nations’. The Dalai Lama smiled; going to Germany seemed like the international platform I was referring to in my note.

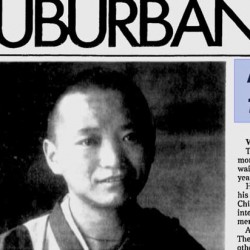

In Dharamsala I learned more about international issues and eventually became a journalist for the Tibetan government-in-exile. For twenty years I wrote about the situation in Tibet before moving to Australia as part of the Australian government’s humanitarian program. It was 2008 and even from afar I have continued to monitor the developments in Tibet and in China, and advocate for Tibet’s freedom.

I have spent twenty-six years in exile, more than half of my life. I have never returned to Tibet and will not do so under the present regime. As a Tibetan, my greatest wish, however, is for His Holiness the Dalai Lama to be able to return to Tibet as a simple Buddhist monk. I also wish for the Chinese leadership to have a big heart, and a warm heart.

A newspaper article on my speaking tour to the US

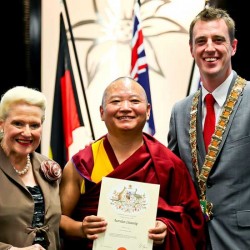

Becoming an Australian citizen in 2013